Ode to Ashes: a Santa Rosa Holiday {Home}coming

Nearly every November since I was 18, I’ve returned to my hometown of Santa Rosa, California for an annual Thanksgiving pilgrimage. No matter the length of my visit, I’ve called it my “grounding period”: my yearly trek West to recalibrate where I come from and dig my soles into the terrior of who I am, no matter the chaos of life. Because the red clay soil of the acre-and-a-third plot in the Hidden Hills where I grew up—in bucolic Sonoma County surrounded by small vineyards and golden valleys—has always been the special place that has made me complete.

I have ventured confidently so far away from home with abandon as I always assumed that my childhood home that I grew up in with the same parents my entire life would be forever waiting for me.

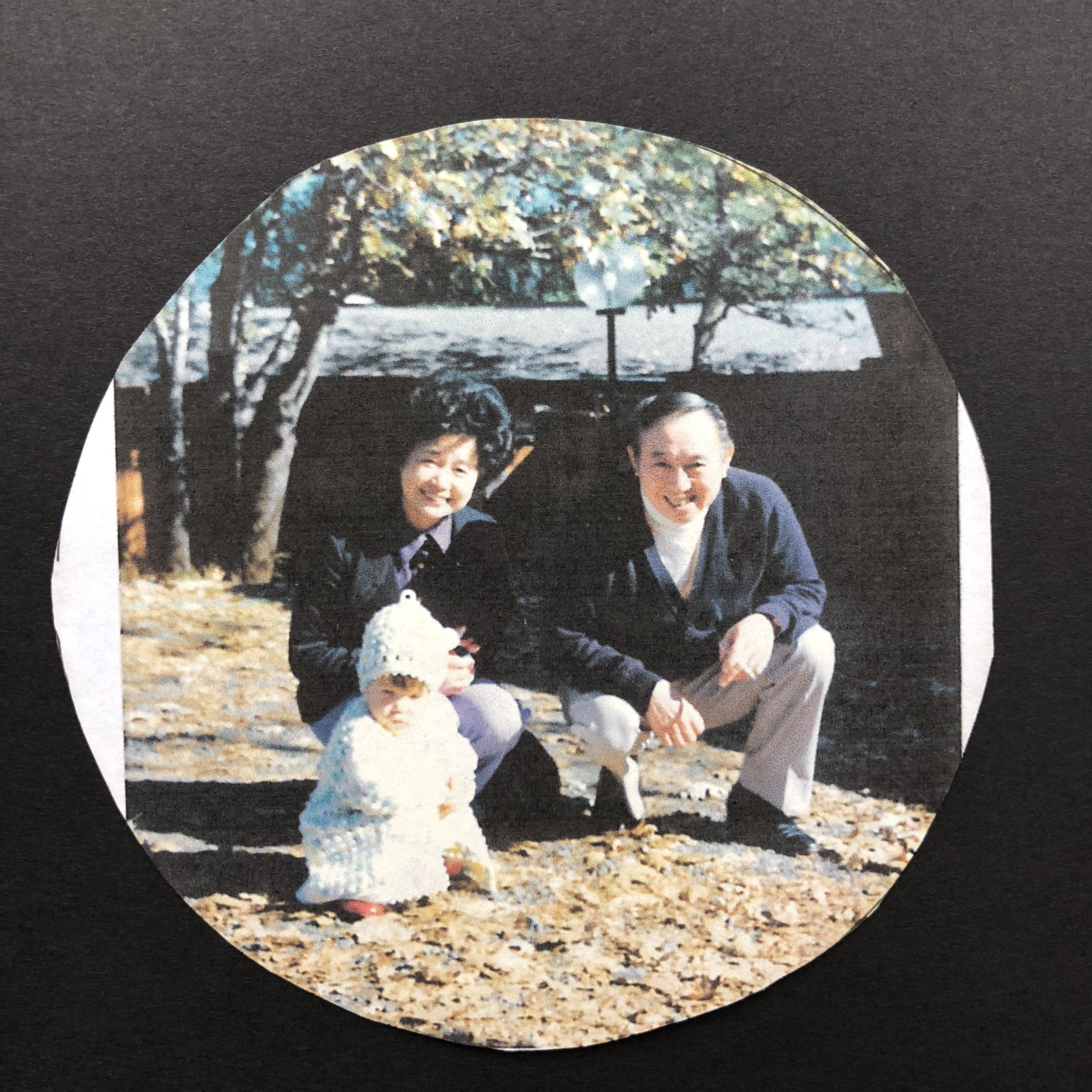

Michael Lin, Circa 2003

But this Thanksgiving would be different.

On October 8, 2017, when the Tubbs Fire blazed its unspeakable force through the region, my parents, Mary Ann and Dr. George Goodman, fled for their lives by chain-sawing—with the help of neighbors—their evacuation path through a felled tree with the clothes on their backs. The entire horizon to the north burned with flames as they descended into Santa Rosa proper, uncertain of their home’s fate.

After confirming my parents’ safety when my mother called the following morning from the Santa Rosa’s Finley Center Shelter, I experienced brief flashes in my mind of things potentially lost. Baby pictures. A medallion autographed by Audrey Hepburn. The paulownia wood plaques that bear my mother’s and my professional Japanese dancing names in calligraphy.

The kaidan dansu.

I am half Japanese and the house my parents built in 1970 as my father established his psychiatry practice in Santa Rosa is a testimony to my rich, ethnic heritage. It was filled with Japanese artifact and antiques, unique, one-of-a-kind treasures collected over a lifetime of travels. Hundreds of kimonos and tea ceremony utensils. Tansu or chests. Family heirlooms.

A very small sampling of the countless kimonos lost: my mother and I are standing center. Hanayagi Juteika Kai, San Francisco Cherry Blossom Festival, Spring 1978.

Among my favorites was the kaidan dansu, which was originally a stairway in an old Japanese home that doubled as shelving within the stairs. (You know my people, so very clever with every use of space even hundreds of years ago.) I wondered about this tansu and my mother ached for it too.

After a week of my parents not being able to access their home due to police roadblocks and downed power lines, it was through satellite technology that I, living on the East Coast, was able to confirm that my childhood home was burned to ashes. From neighbors’ stories on message boards, it had likely succumbed within an hour of their evacuation. I called my parents to relay the news.

***

Though we are but a family of three, I never felt lonely growing up miles outside of town in the country. There was a neighborhood gang of kids and our home always felt the hubbub of activity. My mother, a teacher of both Japanese dance and tea ceremony was forever attracting people for lessons, gatherings or parties.

The Japanese tea parties were perhaps among the most remarkable.

Our dining room transformed from a wood dance floor into a tearoom laid with straw tatami mats with two ceremonies occurring simultaneously. Maximum peace and reverence were required in the morning while the iron kettles hissed and matcha tea sipped: even from the young children, even from the spouses who didn’t do tea and watched sports in the other room.

In the afternoon it would be time to eat, and like a dropped Perrier bottle the day’s silence would slip away, and everyone’s personality exploded to the surface. My mother’s counter-style desk in the family room would transform into the ultimate, 1970’s Japanese-American potluck: teriyaki chicken, potato salad with cucumber and radish, diamond-shaped rainbow finger Jell-o, casseroles topped with potato chips, homemade Chex mix, chirashizushi rice, Philadelphia lemon cheesecake, onigiri rice balls and floating sherbet punch.

We’d eat until our thin paper plates went soft and then go back for more until our stomachs stretched our elastic rompers. We laughed until it was too hot and had to go out onto the deck gasping for the cool, coastal air and another cup of Hawaiian Punch to re-stain our lips. We’d chase until we ran out of spaces to hide, including the two secret hallway closets that locked flush with the wall: the James Bond feature of the house. How we kids could stay flushed with secrecy and hands clasped over our giggles inside of those…to the confusion of every new young guest who couldn’t find us and some adults too!

My Grandparents, Peggy and Gingi Mizutani, with me on the then gravel driveway. (approximately 1974)

My folks smartly designed our house in the shape of a “Y” so I had one end of the house and they the other. My walk down the hall represented many things, but mostly it meant help from my dad in his den. He was and remains so well versed in all things math, science and literature, and I’d hunker in his office with its comforting smell of paper, camera equipment and his leather desk blotter and sort out the complexities of the day. It lacked seating and I’d often have to stand—books and binder awkwardly in hand until he wrapped up a patient call—but it was worth it.

Sometimes my visit had nothing to do with homework. He’d squeak back in his wooden office rocker, nod and listen as I spoke nonsensically about something followed by uncontrolled tears. Those walls flanked by his filing cabinet and my mother’s sewing machine absorbed so much. Only at the end of my sessions would he utter a few words of open-ended questions and sound advice. I always felt better and always felt heard, as if he’d gently sewn up my leaky parts.

Over the years, he replaced his extensive collection of self-shot floral photography with pictures of my half sister Susan and her beautiful family, my school photos and eventually pictures of my husband and children. Now, when I think about it, his office was plastered with our faces…with barely a square-inch for anything else.

There were few upgrades: the house was that solid. But the 60s shag carpet—red and yellow in the family room (the colors of Zoom!) and black and gold in the dining room—eventually gave way to hardwood floors and costly central heating switched to a cost-effective wood stove in the early 80s followed by a less labor-intensive pellet stove in 2009.

My mother and a sleeping, one-month-old me and the black-and gold shag carpet, before our tokonoma or altar with ceremonial dolls: Japanese Girls’ Day, March 1973

The wood stove days, which was when I was around, required round-the-clock work to keep the house warm, with the first person up in the morning stoking the dying embers to the first person home from school or work checking on its status. The last person before bed raked down the mountain of fiery coals and fed the stove with wood logs to last the night.

“So much time spent concerned for fire and to think we were in the end consumed by it.”

It wouldn’t seem so hard to heat our single story home aside from the expansive 12-foot-high cathedral ceilings of exposed redwood. But if it weren’t for those sweeping ceilings, I wouldn’t love rain the way I do. The combination of the ceiling height and simple tar and gravel roof made a storm sound like it was in the room: trickling, tinkling, plopping right onto your head. I couldn’t get enough. I would slide open my bedroom window to hear the rush of the raging brook at the edge of our property down the southern slope, as I drifted off to sleep during a rainstorm. It was my very own white noise machine before white noise machines, only real.

When friends came over to play, my mom sent us outside among the trees, and it was an endless source of magical entertainment. On that southern slope just above the brook was a grove of fragrant bays that grew so densely you could swing from one to another; I called it my “fairy forest” and imagined all kinds of dwarfs living among the roots. The Manzanita trees with their low profile and peeling bark, appealed to restless fingers, their curvy branches perfect for makeshift seating. The oaks just off of my parents’ bedroom actually bowed to the ground and served as balance beams, prolonging the end of many play dates: try and tear your kids off of one of those! And don’t get me started on the pines that were seemingly made for climbing like stepladders to the sky with their evenly spaced branches, smooth bark and lightly sticky sap.

It’s a favorite story of my father’s the time when I climbed the perfect pine on the southwestern corner of our property so high so as to become a pendulum at the top—swaying gently from side to side. With entire valley views of neighboring vineyards, the Shinabargar’s lake, the Foothills across the way bathed in sunset, I couldn’t give it up despite my parents’ pleas for dinner: my responses drowned out by distance and wind song anyway. After dark, I eventually descended for supper. Were they worried? I suppose. But it was that kind of childhood, where I often came in with grease bush flowers in my hair and played outside until I couldn’t pedal my banana seat bike past the darkness.

As I head home on a plane, not having seen the ashes of our former home, this is how I wish to remember her. The redwood exterior. My mother’s kokeshi doll collection. My dad’s music. My parents’ sun-drenched bathroom. My white leather baby shoes. The rear door that closed with a quiet click.

Here I am blue-eyed and eight months old, dressed like a doll in a bassinet on the front stoop. I’m holding my white bootie pried from my foot.

A mini-tornado once brought a burst of purple wildflowers that thereafter bloomed every spring. Who knows what will grow on this land in the wake of the fires? Who knows if my parents, now in their precious golden years, will choose to rebuild?

All I know is that when I close my eyes, I can still see her standing.

My first visit post-fire to the site of our former house on November 19, 2017. This is the same vantage as the opening picture.

Thanksgiving Day 2017. The pole to my right was a globe-shaped light at the top of the walkway we used to welcome visitors.

Green in rocks: first signs of new life nestled in the boulders along the driveway, Nov 2017.

After some delays, the land is at last prepped for the rebuild, which will commence November 2018. My parents are looking forward to their return.

Updated October 8, 2018 on the one-year anniversary of the Tubbs Fire. Originally published in The Huffington Post.